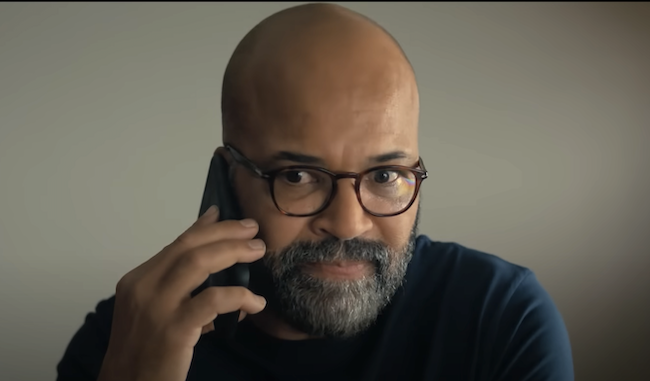

Escaping Out of the Past (1947)

Spoilers coming.

Oh Jeff, I get why you fell for Kathie (Jane Greer). That sexy voice, her air of mystery, those all-white get-ups, vacation drinks, and her nonchalant response to your chase. You really had no hope, did you? Especially once she started toweling you off from the rain.

Yeah, you were a goner, my friend. That was a given.

But I give you credit. You saw her shoot your former partner and realized too much siren for me. You viewed her clearly after that. When your new, sweeter lady love defended her by saying, “She can’t be all bad. No one is,” you (justifiably) answered, “She comes the closest.”

You are right that you were a chump, falling for a homicidal moll’s lies, but honey, in the world of noir suckers, you are Albert Einstein. You learned. You improved your life and your dating judgment (a lot of us don’t make it that far).

Problem is, my friend, you need to work on your shadiness. The detective career is not one in which fisticuffs save you from a bent former partner. You don’t have to kill, but you must learn some trickery and bluffing. To be honest, I’m not sure how you’ve remained above ground this long. I might not approve of Kathie’s answer, but I understand why she thought your self-defense inadequate.

You said it yourself when Ann’s wannabe boyfriend threatened, “I was going to kill you.” You quipped, “Who isn’t?” In those two words, you captured the gumshoe life, in which craftiness and sketchiness are survival requisites.

Luckily, you do have a key asset, Jeff. You are a planner. I need you to remember that neither Whit, nor Kathie, nor any of the henchmen involved have this basic quality. They live on spur-of-the-moment, unerringly bad decision making.

Let’s take your nemesis, Whit. He hired you, a ridiculously attractive man with sleepy eyes and a sultry voice, to retrieve his already traitorous girlfriend. (As my sister says, “That’s like sending Cindy Crawford to get your boyfriend.”)

You soon discovered she was a viper, didn’t you? Whit did too. She’d already nearly killed him. So what did he do when he discovered all the additional murderous shenanigans she’d been up to? He forced this woman into a corner, thinking what? She’d say, “Okay, honey. Off to jail I go”?

I know he looked like he was intelligent, Jeff. But he really wasn’t. And his surviving buddies are even dumber. They just outnumbered you with this tax killing plot. They didn’t — in any way — outsmart you.

Why then, Jeff, after some unlucky moves and bad timing, have you let the fatalism get to you? When Kathie said, “Let’s get out of here” after killing Whit, what did you mean by asking, “There’s someplace left to go?”

Of course there is, Jeff! You surely can double-cross a sociopath with no impulse control. This is no Phyllis Dietrichson, my friend. She’s not going to out-connive you. And do you honestly have a problem setting her up for the three killings she is either solely or jointly responsible for? Is calling the police so that you and she will die in a shootout a more ethical plan? Do you think any of the henchmen left care enough about Whit’s honor or have brains enough between them to hunt you down?

I know you think you can’t escape your past — that once you get into bed (in your case, literally) with evil, you don’t have a shot unless you go full-scale monstrous yourself and outsmart them all, Red Harvest (or its imitator, Miller’s Crossing)-style. And you’re too good of a person to go that route.

But do you need to? Most of your enemies are dead. Your fate is not as determined as you think. Your odds are far better than Kathie’s were in her gambling efforts in Acapulco. Her fingerprints are all over that home, and angel face or not, she is a gun-loving gangster’s moll (in a terribly sexist age), which doesn’t make for the best defense.

I know this is the noir way, Jeff: You must play the man defeated. You must see killing her (even indirectly) as the only escape from her wiles and the only protection for the woman and friend you love. I get it, Jeff. It makes for a good movie.

But you said it yourself, Jeff: “There’s a way to lose more slowly.”

And in this case, you actually had a chance to win.