3 Classic Anti-Valentine’s Films for Sex and the City Fans

Single or attached, I’ve always loathed Valentine’s Day. When single, I’ve wondered why our couples-obsessed culture needs a day devoted to twosomes. When attached, I’ve pondered why I should celebrate en masse what’s supposed to be intimate. Therefore, my three recs today are for those who share my distaste for the day:

Female Bonding: Stage Door

For those who’d rather split a few bottles of wine with pals than brave pink-and-red-bedecked nightclubs this Friday, I recommend Stage Door, a film centered on women who live in an all-female boarding house as they try to make their big breaks on the stage.

The heroines’ choice to remain single (and have casual boyfriends only) is celebrated rather than reviled by the film. If anything, the film mocks marriage. But don’t just view Stage Door (1937) for its politics; watch it to see the phenomenal cast interact: Ginger Rogers, Katharine Hepburn, Lucille Ball, Eve Arden. (The latter you may recognize as the principal in Grease; in her youth, she was always the smart-talking sidekick.)

The dialogue is so slick and cynical and quick that you’ll have a hard time keeping up with the one-liners, as when wealthy Terry’s (Katharine Hepburn’s) haughty tone annoys her impoverished fellow residents. Jean (Ginger Rogers) is not one to let an insult slide. When Terry snootily states, “Unfortunately, I learned to speak English correctly,” Jean fires back, “That won’t be of much use to you here. We all talk pig Latin.”

While the more famous classic movie about female friendships, The Women (1939), favors marriage with unfaithful partners over relationships with backbiting friends, this feminist flick celebrates the humor and loyalty between single women. In fact, I would argue that Stage Door’s women are in some ways more liberated than those in Sex and the City. Watch and see if you agree.

Revenge as Art: Gilda

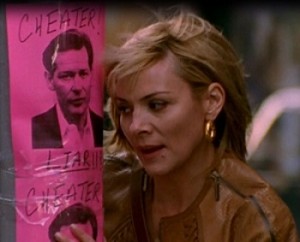

I enjoyed Samantha Jones’s (Kim Cattrall’s) revenge on boyfriend Richard Wright for his infidelity in Sex and the City: the dirty martini in his face, the papering of the city with posters describing his behavior.

But this kind of takedown is kitten play compared to the work of Rita Hayworth in Gilda.

Like Samantha, Gilda (Hayworth) is in full command of her sexuality; it’s not difficult to discover why this WW II pinup was dubbed “The Love Goddess.” But her treatment of her ex, Johnny, is far more ruthless than her modern counterpart’s. First, she marries Johnny’s boss; then, she flaunts her affairs with other men to torment him further.

Gilda is so skillful a manipulator that you root for her to get what she wants, even if the ex she desires is no prize (and no mean manipulator himself).

Here’s an anti-Valentine’s Day conversation if ever there were one:

Gilda: “Would it interest you to know how much I hate you, Johnny?”

Johnny: “Very much.”

Gilda: “I hate you so much I would destroy myself to take you down with me.”

I think Samantha would be impressed.

Exploiting Men: Baby Face

In an early episode of Sex and the City, “The Power of Female Sex,” Carrie’s fling has left a tip on her bedside table and she’s feeling ill at ease with the implications. The four friends discuss whether it’s ever acceptable to use your sexuality to get ahead. Barbara Stanwyck’s character in Baby Face (1933) has no such qualms: She leaves her hometown for NYC with the aim of doing just that.

The shocks accumulate quickly as you watch Baby Face: Lily’s (Stanwyck’s) father has been prostituting her since she was fourteen. A grandfatherly figure in her dad’s speakeasy recommends she leave home to sexually exploit men for personal gain, quoting Nietzsche to back his case. Once in New York, Lily takes quick steps to follow his advice, seducing the HR assistant in a bank to get a job, and then sleeping her way floor by floor to the top. (The camera helpfully pans up to highlight each floor as she ascends.)

You might expect the movie to make the heroine suffer for her behavior, given the date of this film, but she is unmoved by the heartbreak and eventual tragedy she leaves in her wake (among her victims is a smitten John Wayne). Men have used her all her life. Lily figures it’s her turn, and the film clearly sympathizes with her reasoning. She calmly goes about her business of seducing men, accumulating jewels and bonds, and sharing her successes with her best friend, Chico (Theresa Harris).

Here’s a typical exchange with a discarded lover who stops by Lily’s apartment:

Ex-Lover: “It’s been brutal not seeing you.”

Lily: “Yeah, well you better get used to it.”

When he returns and offers marriage, Lily answers, “So you want to marry me, huh? Isn’t that beautiful. Get out of here….”

This is a strange film with a number of flaws, but you won’t care; it’s too much fun to watch this predator in action. (Be sure to watch the pre-release version; it’s much better.)

What are your favorite anti-Valentine’s films?