M: A Serial Killer’s Story about Us

I’ve always been puzzled by The Silence of the Lambs becoming more successful than Manhunter. The latter’s subtlety, especially Brian Cox’s portrayal of Hannibal Lecter, was far more alarming to me than the campy style of Anthony Hopkins. The former I could mistake for a normal human being, making his monstrosity all the more terrifying. Yes, I might jump out of my seat during The Silence of the Lambs, but Manhunter is the stuff of lasting nightmares.

The story is better too, as the deeper fear is not of the serial killer, but of being like him. Mann (and novelist Thomas Harris) question whether investigator Will Graham’s (William Petersen’s) uncanny understanding of psychopaths’ minds means that he has the same dark passions. And of course, that leads to us: Does it make us somehow sick to be interested in a killer’s psychology or his/her capture, to read the stories and watch the films? And if that doesn’t mean we share his/her pursuits, what form does our sickness take?

Perhaps that’s why I think Michael Mann fans would be drawn to M, the 1931 film that begins with a frightening depiction of a child killer, but ends by questioning the wider society that is hunting him. Like Mann, director Fritz Lang did not employ every bell and whistle at his disposal, did not play melodramatic music in the background or make us witness gore or the frightened faces or cries of children. Instead, this director in his first talkie displayed a restrained artistry: an image here, a sound there—just enough, and never more. The result is a haunting film that lingers long after its conclusion.

M begins simply, with a disturbing children’s game about a murderer. A woman tries to shush the kids because what’s going on in Berlin is too similar to their words: a child killer is at large in the city. The camera then narrows in on mother Frau Beckmann (Ellen Widmann), who displays her love for her child, Elsie, through her loving arrangements for the child’s return from school: washing the clothes, preparing a meal with care, peering up at the time with a smile.

The film cuts to Elsie (Inge Landgut), the only sound her ball hitting the pavement. The almost complete silence of these scenes is paralytic to the viewer. We don’t see the killer, just a posting about children’s disappearances obscured by the girl’s ball and a man’s shadow. The man praises the ball; he asks Elsie her name.

As the time passes when Elsie should have arrived, Frau Beckmann looks at the clock. She asks returning kids whether Elsie was with them. They say no.

We see the murderer buy Elsie a balloon from a blind man (Georg John). We hear very little but Elsie’s thanks as the killer whistles Edvard Grieg’s “In the Hall of the Mountain King,” which will later have us jumping, like we did in hearing the arrival of Jaws.

Meanwhile, the mother smiles when a salesmen stops by her door, thinking him Elsie, and can barely attend to his words before she questions him about her daughter. She calls down the stairs to her.

Now overcome with worry, she opens the window.

As she calls, “Elsie!!” the first of several silent shots tells viewers that Elsie will not be coming home.

The images are harrowing; the viewer feels horror: at the child’s death, and the mother’s loss. The ethics are simple: the killer is evil, the mom and child good. The spare use of sound and imagery contribute to this clear-cut moral universe, which Lang is about to disrupt, for this film, we soon discover, is not about the murderer: it’s about the citizens, criminals, and police who pursue him.

Next, we hear a newspaper hawker talking about the crimes, as the murderer (Hans Beckert, played by Peter Lorre) whistles his tune and writes a letter to the paper explaining that his spree is not finished. As friends around a table discuss the murders, they are soon viewing each other with suspicion, one even accusing another of being the man in question.

A mob mistakes an innocent elderly man for the predator, simply because he answered a young girl’s question.

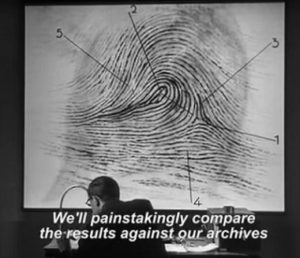

The shouts of the crowd are then cut short, as the words of the murderer’s letter appear on the screen in absolute silence. When the commissioner begins to discuss his investigation on the phone, we see the police in action: tracing the fingerprints on that letter, investigating the handwriting, scanning the crime scene, interviewing confectioners due to a wrapper that’s been found.

As the killer’s pathology is explained, we see him closely for the first time; he makes faces in the mirror, as if trying to see himself as others do. The film’s writers, Lang and spouse Thea von Harbou, achieve a high level of verisimilitude that makes the film resemble today’s police procedurals. (Some say, despite Lang’s denials, that this was due to their attention to the extensive media coverage of serial killer Peter Kürten.)

But all of the police’s efforts prove fruitless. Desperate, they soon resort to frequent raids to catch the child murderer. Lang covers these raids beautifully, beginning with a silent scene of a prostitute soliciting, and segueing into the police marching down the streets en route to the bars to demand papers. The sound finally returns in the form of a whistle to warn customers the police are arriving, after which we hear the uproar of the crowd’s dismay as they try to escape.

A bar owner explains that this treatment of customers is unfair to them and to her, and unlikely to result in an arrest.

“I know a lot of toughs who get all teary-eyed just seein’ the little ones at play,” she explains to a police sergeant, warning, “If they ever get their hands on that monster, they’ll make toothpicks out of him.”

This Cassandra leads us to the next scene: Upset with the disruption to their business, the criminal underworld, led by Safecracker (Gustaf Gründgens), decides they’ve had enough. They’ll find the killer themselves. These mob leaders have a conference to plan their strategy, much like in The Godfather.

Lang cuts back and forth between this conference and a similar one the police are holding about the case, causing the viewer to confuse the two, and then start to wonder whether there is any difference between them.

The police decide that they’ll go the mental health route, finding patients who’ve been dismissed as harmless but have suspicious tendencies. The criminals decide they’ll organize a league of beggars, who, as unnoticed observers of their surroundings, can spot the predator without scaring him. Both groups succeed in narrowing in on Hans Beckert through these means, even as the latter follows a new girl, his silent contemplation of her soon erupting into his signature whistle.

Among the beggars is the blind balloon seller, who, upon recognizing the whistle, sets the alarm, leading to the killer being chased into an office building, a chalked M mark from a beggar having pegged him as the one to follow. The longer the hunt continues, the more the viewers’ allegiance shifts. We don’t want Beckert to go free, but there’s something sadistic about this manhunt, perfectly captured in the large eyes of the predator who has suddenly become prey.

We know now that these criminals are no longer just out to save their business; something more primitive is at play. What happens next is too fascinating for me to give away. But I will say that the film’s treatment of the child killer is surprising; he’s even given a chance to explain his affliction: “Can I do anything about it? Don’t I have this cursed thing inside me? This fire, this voice, this agony?”

Nazi leader Joseph Goebbels, who later offered Lang a job, obviously interpreted the film as less complex in its sympathies than I have. Certainly, there is room for dispute about what Lang was trying to say. But with the Third Reich imminent, Lang (who had Jewish heritage) was about to skip town, job offers notwithstanding. It’s hard not to see in the film’s conflation of police and criminal, citizen and predator, an indictment of the authoritarian regime, especially since Lang’s next film more explicitly attacked it (though, interestingly, facts apparently don’t bear out Lang’s account of his own precipitous escape).

Regardless of his initial motives, by giving the murderer voice at all, Lang questions whether this man might be more than the “rapid dog” he is accused of being, might be in need of a doctor’s care, not a hangman’s noose, as a reluctant defender in the film claims. And since we know the killer is not the subject of this story, we viewers soon turn to the crowd condemning him. Just as there is within this man, Lang seems to imply, there’s a sickness within society. After all, normal German citizens will come to support the Nazi party, including his wife and cowriter. Who is to say any culture isn’t vulnerable to the same manipulation, the same results, given the right fears to make them operate? Whether or not that sickness and those who’ve let it spread are capable of redemption or not, he leaves it to his audience to determine.