The Artist at Play: Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

This post is part of the blogathon hosted by Movies Silently and sponsored by Flicker Alley. Thanks to both for such a great event! Click here to see the wonderful entries of the other participants:

Wizardry. It’s the word that jumps at you while viewing Man with a Movie Camera, the celebrated documentary depicting 24 hours in a Russian city. Unlike the famous magician of Oz, director Dziga Vertov invites his viewers to experience all that his camera—and by extension, all that film—can do. Announcing at the start of his movie that there will be no scenarios, intertitles, or actors, Vertov set out to separate the genre from its roots in theater. The result could have been a movie so meta it became unwatchable to any but film scholars; after all, the director even demonstrates how he obtains shots, even exhibits the film editing process. But this masterpiece is not only revolutionary; it’s also engrossing. Here are just a few reasons why:

It’s a Bird…It’s a Plane…It’s Vertov Behind the Camera

There’s a dizzying speed to the film, images flashing by at such a clip that some contemporary viewers and critics protested. Predictably, some of this speed captures industry, as when the director hurries an assembly line production to Tasmanian Devil haste to capture its unremitting flow. The director thrills at images of transportation, with clips of trains, buses, motorcycles, often with himself in dangerous positions to capture the motion. The thrilling score—I watched the Alloy version—underscores the frantic mood.

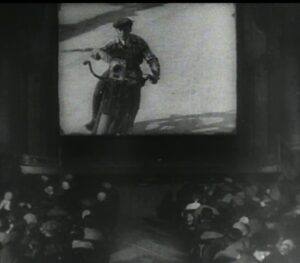

Vertov occasionally slows his pace, even stopping to profile still shots, the film editing process, and those same shots in action in a particularly lovely tribute to the power of moving images.

But it’s in rapidity that Vertov reveals his mastery of form and meaning. He even underscores the brevity of life in a short sequence. We see a couple getting a marriage license.

Directly after, another couple is signing divorce papers; the director zooms in on the estranged wife’s grim expression.

A mourner appears in a cemetery. A funeral passes our eyes. A baby is being born.

The director moves back and forth between the scenes to reinforce the connections. This circle of life takes a total of three minutes.

Realism…with Mannequins

The film begins in a movie theater, priming the audience for a show. We see a Russian city, morning beginning. A woman sleeps in her room; a child does the same on a bench where he’s spent the night. There are scenes you expect next: the bustle of a city beginning, the drudgery of work. And some of those scenes, you get, and each is powerful, particularly portrayals of the mines. But it’s the surprises that keep you watching. Why does the director dwell on creepy shots like this one?

What’s the obsession with washing scenes? (What number of shaving, tooth brushing, and hair cleansing rituals were shot over the years he made this movie to end up with so many in the final product?)

Documentaries can be gloomy, and for a director who attacked fiction and took so seriously his aims to capture truth, Vertov has a surprisingly light touch. You’re struck by the artist’s obsession with grace, revealed through a montage of pole vaulters, high jumpers, dancers, and basketball players.

He revels in a kid’s magic show, in women’s bodies at the beach. He attempted an international art form through his completely novel take on a documentary, achieving the realeast of real. And he delivers: You can’t help but feel fascinated by similarities evident between Russian culture and ours, between 1929 and today.

But like this pioneer’s artistic descendants, practitioners of cinéma vérité and literary journalism, Vertov believed revealing subjectivity was part of delivering truth. He not only affects his subjects by the intrusion of his camera, but our perception of them by which shots he includes, and which he doesn’t. As essayist Joan Didion would explain many decades later, “However dutifully we record what we see around us, the common denominator of all we see is always, transparently, shamelessly, the implacable ‘I.’”

Part of the delight of Man with a Movie Camera is watching subjects’ reactions to his (then novel) camera: the woman who blocks her face with a purse to avoid it, the tiny girl who can’t keep her eyes away.

But the director’s vision is so unique and his quirkiness so evident throughout that you never forget that another artist would have chosen other faces, other moments, would have startled his subjects in other ways, and for other reasons.

Look, Mom! No Hands!

The highly touted innovations with camera work in the film are remarkable in and of themselves. (Who knew so many of these techniques were used so early?) They also serve a purpose, not only illustrating Vertov’s sense of time dissolving, but recapturing for modern audiences the thrill of being at the beginning of a new art form.

They made me think of the Impressionists, freed from the tyranny of having to capture exactly what they saw. The scenes featuring the filmmaker at work are so amusing. Here’s the photographer riding on a moving car! Watch him risk his life to portray that train! I kept thinking of a little kid showing off on his bike, holding his hands aloft for the first time. And just as I thought it, I saw this image:

Because the director’s having fun, so are we.

Because the action is exhilarating, we are giddy. Who but a kid-like grown up could have come up with an animated movie camera in action, or with this delightfully silly image?

Surely, Vertov would be leading the creative team at Pixar today.

Sight and Sound rated this movie eighth, and gave it the honor of best documentary of all time. I am not surprised by either ranking given the vision and experimentation of this film. But that’s not why I’m glad that I’ve seen it. What an experience, to witness so much of life covered, in so little time, and so beautifully. What a joy it is, to a witness the work of a genius with a sense of fun.

Thanks to Kimberly Bastin at Flicker Alley for a screener of the film!