Bergman’s Weird Wife in Stromboli

I’ve always been curious about the film that united director Roberto Rossellini and actress Ingrid Bergman in their illicit romance. How red-hot would an affair have to be to lead to a public censure in the US Senate and a six-year ostracism from Hollywood?

I was prepared for something akin to Mr. and Mrs. Smith (2005), where the chemistry of actors (and new lovers) Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt inflamed the screen.

Of course, I neglected to consider a few things before viewing: 1) the absence of the director as an actor in the film, 2) the film’s very un-Hollywood use of everyday people as actors–in this case, fishermen in Stromboli, a small island off of Sicily, 3) the plot.

The Keystone Cops would have been just as likely to show up as a red-hot romance.

But in one way, I was still on the right track about Stromboli (1950): you can’t keep your eyes off of Bergman, and she IS unbelievably sexy in the film.

The nature of that sexiness is curious because this is a very, very odd movie. I found myself siding with early American critics, who called it dull. I agreed; it was dull. But it was also haunting, with a grim take on marriage quite unusual for its time.

Bergman’s character, Karen, is fascinating because she is one of the least sympathetic, most selfish brides I’ve ever witnessed onscreen. She marries a poor but handsome ex-POW, Antonio (Mario Vitale), to get out of a displaced persons camp.

When he brings her home to his fishing village, she doesn’t even try to be civil–to anyone. She attacks her new groom for taking her there. She tells him this place is terrible, that she’s too refined for it and can’t stay. Kind of harsh right after his release from a camp, huh?

In fairness, the village does suck, at least for Karen. There’s an active volcano that can erupt at any moment. Their house is a shack. There’s little to do or see. The townspeople are super judgy and foreigner-averse, which doesn’t make Karen, a Lithuanian, feel very welcome.

But it’s hard not to pity (at first) the poor husband who just takes Karen’s verbal abuse and hostile glances–especially when he quietly accepts an underpaid fishing job to buy her a better life.

She starts filling the home with the worst decor I’ve ever seen–and hides away her husband’s family photos and religious icons, which she despises. Apparently, this process gives her some pleasure. She’s appalled when he doesn’t love what’s she done, including the weird flowers she’s painted on the walls, kindergartener style. (I told you this film was bizarre, right?) She decides to use a sewing machine in the home of an apparent madam, despite warnings. Then she’s mad at others for thinking she’s loose.

But just when I’m ready to care only about him, her husband proves he’s brutish, like she’s claimed: he beats her for making him look like a cuckold. Now, we audience members don’t have anyone to like in the film.

As for Karen, it’s not long after the house decorating that she begins to plot her escape. Her method is to throw herself at every man who might get her out of there, including–wait for it–the village priest. And the seduction act Bergman pulls is something to witness. I’m not sure how anyone resists it, transparent as her motives are, because this is Ingrid Bergman throwing herself at you, men!! And she has moves. (Narratively, it would have made sense to choose a less attractive actress, but I fully enjoyed full-seduction Bergman. It’s easy to understand how Rossellini fell for her while filming.)

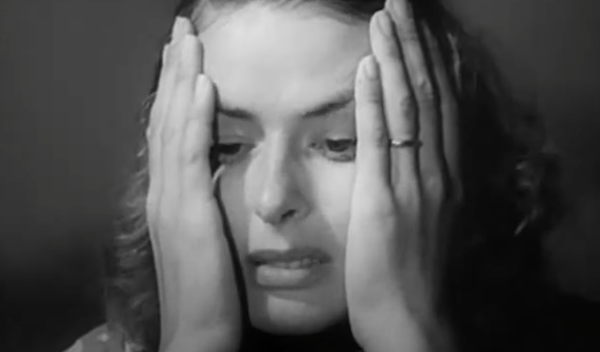

But it’s not just her sensuality that has the audience enthralled by Karen. Her breathless confidence in herself in the face of hostility and discomfort and abuse and foreignness is something to witness. You can’t help but root for her even as you question her decisions. Bergman displays confidence not just through her voice and expressions, but through a kind of ease with her body typical of athletes and dancers. In another world and in another time, you think, what couldn’t this single-minded woman do!? No wonder she’s so angry about her lot!

Unfortunately, Karen soon proves that her poor judgment is not limited to her words and decor. On a lark, she stops by her husband’s job while he’s fishing for tuna with his crew in a ploy to earn his affection. WHO DOES THIS???

This choice is one of the plot devices that seems to be an excuse for Rossellini to include a beautiful neo-realistic scene. It’s easy to understand Rossellini’s reputation as a director when it comes to cinematography. It was fascinating to watch the brutal and dangerous process of catching these huge, gorgeous fish and killing them as the refined wife looks on, horrified.

Later gorgeous scenes include when the volcano erupts, and the town flees for the sea. The escape is fascinating and frightening to watch, and beautifully rendered. (In typical fashion, Karen is only concerned about her own rescue when she sees motorboats.)

**Spoilers coming**

Stromboli is most famous for its ending. Fresh from volcano PTSD, Karen takes off, despite being pregnant. She heads over the still-active volcano alone to get to the side of the island where she plans her escape. She dumps her suitcase in exhaustion after breathing in copious amounts of smoke. She passes out after admitting defeat.

But when she wakes, she calls aloud to God, asking for strength, proclaiming that her experience has been too awful to endure and that she must depart. Whether she really means awful for her or for her unborn child (or for both) is unclear despite her words. Hollywood later added a voiceover suggesting she returned to her husband, a disturbing “happily ever after,” given his violence and decision to forbid her exit by nailing the front door shut while she was inside.

But I don’t buy Hollywood’s interpretation. Karen seems more intent on the birds above her, on the flight still possible with God’s help. The end is ambiguous, it’s true–I can’t be sure I’m right. What ISN’T ambiguous is how miserable Rossellini makes marriage look–which is interesting as he’s breaking up Bergman’s and his own.

Regardless of what anyone makes of the film, Bergman’s performance is unforgettable, and not to be missed by her fans. The extended final scene of her climb and pleas is breathtaking: her resignation, her desperation, her anguish, her hope. This woman deserved all of her three Oscars and then some, and it’s a pleasure to watch her commanding the screen in this stunning finish. If nothing else, watch that.

This post is part of The Wonderful World of Cinema‘s 6th Wonderful Ingrid Bergman Blogathon. Check out the other celebrations of Bergman here!