What does the term gold digger really mean, in the context of the Depression? Today we think of Kanye’s gold digger; buying gold and liposuction, maybe holding a lap dog and wearing furs; not a showgirl escaping destitution. For a musical, Gold Diggers of 1933 is surprisingly earnest, managing to both entertain and make us empathize with the plight of its subjects—and by extension, its audience. As a producer in the movie assures his performers, “I’ll make ’em laugh at you starving to death….”

The film begins with showgirls performing in gold-coin bedecked, barely-there costumes. They’re singing the famous, “We’re in the Money,” led by Fay (Ginger Rogers).

We suspect there’s irony at play; after all, Fay sings a verse of it in Pig Latin.

Rogers’s language play

And of course, we’re right to be skeptical about those claims: before the song ends, the creditors bust in, close the show, and guarantee not a soul singing will be anything but broke.

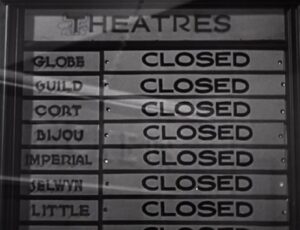

Clearly, this isn’t the slight film the title, or its greatly inferior sequel, might lead a modern viewer to expect. I was just reading about Girls, wondering if I could handle another season of Lena Dunham’s show about over-privileged, under-motivated friends in the city. I kept thinking of that show when the camera panned from the closed show to a small posting illustrating these singers’ (dissimilar) lack of options:

The camera then turned to a letter beneath the flat door of three of the performers, a rent demand from their landlady.

All three are sharing a bed. They wake up late, with nowhere to go. “Come on, let’s get up and look for work. I hate starving in bed,” gripes Polly (Ruby Keeler).

“Name me a better place to starve,” replies Trixie (Aline MacMahon). The famished roommates steal milk from the neighbors. Trixie reassures the others it’s okay because the milk company “stole it from a cow.”

I know that there’s a place for anyone’s woes; that life (and the films and shows depicting it) is not a comparison game. But the scene reminded me of why Girls so often, despite its cleverness, has left me flat. I’m just not very engaged by women without ambition or integrity. But women who can manage wit when they’re living on bread and snatched milk? Yes, please. Give me more.

When Fay arrives to announce a new show, the women band together to give one of them—Carol (Joan Blondell)—a complete outfit to impress the producer. They’ve hocked too many stockings and dresses to do anything else.

A tearful Carol calls to tell them it’s true that there’s work and that the producer, Barney (Ned Sparks), is on his way; however, he soon confesses he has no funds to start the musical. As eloquent as Carol’s response is to his trickery, her expression is even more so:

Luckily, the women’s singer-and-composer neighbor, Brad (Dick Powell) is available. He impresses Barney with his music, especially the tune which best fits the producer’s Depression theme. More importantly, Brad offers the money to put on the show.

(Just an early spoiler) Brad is secretly a member of a wealthy family, and his proud brother, Lawrence, is not pleased to see his sibling in a musical, and even less pleased the boy is in love with Polly (Keeler). Lawrence’s (Warren William’s) banker, Faneuil H. Peabody (Guy Kibbee), convinces his client all showgirls are gold diggers, and Lawrence therefore rushes to quash the romance.

The two men go to the girls’ apartment to pay off Polly, but mistake Carol for her. Enraged by their condescension, Trixie and Carol decide to pretend Carol is Polly and take the two haughty men for all they’re worth to teach them better manners (and teach us that the title of this film is as ironic as its opening song).

MacMahon as Trixie can occasionally grate, but Guy Kibbee is wonderful as the elderly, lascivious lawyer, the man whom Trixie feels is “the kind of man I’ve been looking for. Lots of money and no resistance.”

Trixie plans to marry the banker in spite of her lack of attraction for him (“You’re as light as a heifer,” she says when she dances with him). She just needs to fend off Kay (Rogers), who wants a meal ticket too.

Carol has no such plans. She’s just angry. The film wants us to understand that Kay and Trixie are just desperate—but understandable—exceptions to the rule. Most of the showgirls, far from being the “parasites” Lawrence assumes, are as ethical and proud as Carol and Polly are. Slowly, though, Carol, in spite of herself, begins to fall for the handsome snob.

The women’s antics are entertaining, especially when they fool the men into buying them pricey hats. But the men’s conviction they’re hanging out with these lovelies just to do Brad good is even funnier. Since this is a pre-Code film, there’s no dearth of skimpy clothing and sexual references. Lawrence soon passes out drunk after confessing love for Carol, and she and Trixie move him to their bed, knowing he’ll assume he’s had sex with faux-Polly and will be too compromised to object to Brad marrying the real one.

Sexual innuendo is evident throughout the musical numbers in the show, especially since this is a Busby Berkeley film. One of my favorite acts is about couples “Pettin’ in the Park.” When it rains, the women retreat to change, returning to their men in metal dresses.

The men are frustrated and outraged they can’t access their partners’ bodies.

Luckily for them, a peeping toddler (yes, you read that right) gives the star (Powell) a tool to break through his love’s (Keeler’s) metal, which he’ll presumably pass to the others.

But Berkeley doesn’t keep with this light tone for all of his numbers. The film ends with the Depression tune that Barney promised, with Carol singing, “Remember My Forgotten Man.”

Alone on a street in seductive attire, she first talks, then sings, “Remember my forgotten man?/You put a rifle in his hand./You sent him far away./ You shouted, ‘Hip hooray,’ but look at him today.”

Carol defending a forgotten man

The song moves from one woman, to another, then builds into an anthem of men and women attacking the government for not doing more to help the veterans and farmers who’ve worked hard for their country, only to end homeless in breadlines, unable to support the women who love them.

Their women are left not only witnessing their men’s suffering, but with children to support as well as themselves–alone. Carol’s provocative attire and presence on the street are no accident, of course. There is one type of work she can get without her man.

The song is heartbreaking. How rare to find a movie, a musical, that captures the national plight like this, especially after such light fare. But of course, the song is also a reminder that there was nothing truly light about the whole film. Is Trixie a greedy gold digger for wanting a rich husband rather than starving as she waits for a show not to be canceled? The oldest and least attractive of the bunch, she knows she must beat Fay to the lawyer’s libido, or she’s probably headed for the streets. The relatively happy unions of these women don’t blind the audience to the fact that there are a lot of girls in that show, a lot of women without secretly-rich neighbor-lovers, without pliable elderly bankers, but with landlady’s notes waiting for them under the door.