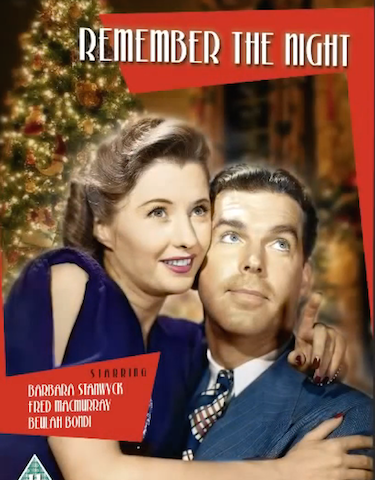

A Classic Christmas Romance for Any Day

How do you create a Christmas film that is sentimental, without dripping it in eggnog? Especially when you’ve agreed to make it a romance between a shoplifter and her prosecutor, and set it in *gulp* Indiana, which is peppered with cornpone clichés in every cinematic portrayal? Miraculously, Remember the Night (1940) not only steers through these dangers, but manages to be fresh, original, funny, even moving, thanks to four very wise decisions:

1. Trusting Screenwriter Preston Sturges

Tone is a tricky thing, and Sturges was a master at it. He knew how long he could get away with sentiment, when to cut it with humor.

Caught trespassing

He developed complex leads. John, the hero (Fred MacMurray), is introduced to us as a wised-up NYC DA. He comes across as jaded and unfeeling in his treatment of the repeat shoplifter (Barbara Stanwyck). Yet we can’t help but laugh at his humorous take on the defense attorney’s silly ruses to win the trial, and admire his own tricks to postpone it. His decision to later assist Lee reveals a soft side Sturges further develops when the character is home with his relatives.

The shoplifter, Lee, is played by Stanwyck. I know I don’t really need to say anything else (see below), but during the trial, expressions–hope, disillusionment, amusement, anger–move quickly over her face, revealing that her hard life hasn’t completely hardened her. When John, feeling guilty about her jail time over the holidays, springs her until the second trial, she (thanks to the dirty mind of his bondsman) ends up at his apartment. At first, she assumes the worst. But when she discovers the mistake, she starts to enjoy John’s company, and the two end up traveling home to Indiana for Christmas–he, to see his beloved family; she, to visit the mother she hasn’t seen since she ran away.

In other hands, the plot wouldn’t have worked; I wouldn’t have even watched it had someone else written it. I am tired of portrayals of my home state, which is typically drawn as either the embodiment of (a) homespun happiness or (b) hickville. But Sturges avoids the trap by giving us a variety of Hoosiers. Stanwyck and MacMurray are both streetwise, smart, and sophisticated. While John’s mother and aunt initially appear to be simple souls, neither is a stereotype. Sturges gives each insight, making the scenes with them far more complex than they initially appear, and allowing us to enjoy the sentimentality of a homey xmas when it comes. Similarly, the scene with Lee’s cold mother, which could have played as far too maudlin, is beautifully understated and short.

True, Sturges does have some missteps. He makes the servant/helper Willie a rube (Sterling Holloway). He’s even an aspiring yodeler. Seriously? I decided that Willie was OK because he canceled out John’s simpleminded African American butler in New York, Rufus (Fred Toones, one of Sturges’ stock players). (I’ll take cinematic classism over racism any day.)

As the director, Mitchell Leisen doesn’t get enough credit for the film’s quality (nor did he get enough credit for Easy Living or Midnight). I’m particularly impressed with his choices of which look to linger upon, which face to highlight, in which moment. But more importantly, the story’s pacing–one of its chief charms–is due to Leisen choosing to cut some of Sturges’ script, according to Ella Smith. Given that there’s a breeziness to many of Leisen’s comedies, it’s hard to argue pacing is all to his writers’ credit. Surely, too, it should be seen as an asset when a director trusts his writers, as Leisen surely did. According to Smith, he even agreed to keep the title, despite having no idea what it meant.

2. Selecting Talented Actresses as the Resident Hoosiers

Character actresses Beulah Bondi (John’s mom) and Elizabeth Patterson (his aunt) would win acclaim for The Waltons and I Love Lucy, respectively, later in their careers; it’s not hard to understand why. The two, familiar faces in a number of 30s and 40s hits, mesh so beautifully it’s hard to believe they aren’t really sisters. Watch Patterson’s reaction when she shares a dress from her past with Lee, or Bondi’s worry as she watches her son’s increasing attraction to the shoplifter he’s prosecuting.

3. Casting an Understated Actor as the Hero

MacMurray is good in everything. He and Stanwyck would, of course, pair up again for the landmark noir, Double Indemnity. But this is the performance that won me over. Watch the scene when he meets Lee’s mom, how gracefully, subtly he handles it. The brevity and tone of the scene, of course, help, but another actor would surely have overplayed his reactions. Instead, MacMurray’s smooth, simple words, with just a twinge of emphasis, say just what needs to be said: this mother is a monster, and Lee’s criminality is no longer mysterious. (Spielberg would have launched a huge, weepy score; thank you, Leisen, for not doing so.)

4. Choosing Stanwyck as the Star

The soul of the story is Stanwyck’s. She has to sell the moral quandary: Will she give in to romance with John, knowing it will kill his career? We have to care about her, about her struggle. We have to root both for the couple’s happiness AND for morality winning the day. We have to sympathize as John’s occasional denseness hurts her feelings, and laugh at her quick bursts of anger when it does. We have to even let some realism in (how’s that for a rom-com shock?): acknowledge that love does not, in fact, conquer all; in fact, sometimes it’s very much in the way (at least temporarily). It’s quite a balancing act Stanwyck must play; if she gives him up, the movie could become soapy very easily. If she doesn’t, how could her performance come across as real; how could we continue to root for her? Other actresses might have missed the target, but not this one. Sentiment, comedy–the woman did it all, beautifully, and as naturally as any performer I’ve ever seen. Because of her, you will love the film, December 25th or July 2nd.

At the Golden Globes the other night, Tom Hanks mentioned Stanwyck’s name in his fantastic presentation of the Cecil B. DeMille Award. He explained that the winner, Denzel Washington, was one of an elite group of great actors who “demand” our attention, who can’t be duplicated. “The history of film,” he said, “includes a record of actors who accrue a grand status through a body of work where every role, every choice is worthy of our study. You cannot copy them. You can, at best, sort of emulate them….Now it’s odd how many of these immortals of the silver screen, of the firmament, need only one name to conjure the gestalt of their great artistry. In women, it’s names like Garbo, Hepburn, Stanwyck, Loren.”

The speech, of course, justified watching the rest of the show. I’m not always a fan of Hanks’ work (he’s far better in comedy than drama), but his wisdom is evident. So was Sturges’; in his third turn as a writer-director, his first with a female lead, he would cast Stanwyck as his Eve and make movie history. The Lady Eve so impressed us all that this quieter, earlier effort has been forgotten. It shouldn’t be.

This post is part of the Barbara Stanwyck blogathon, hosted by Crystal at In the Good Old Days of Classic Hollywood. Check out the fabulous entries on my favorite star at her site.