The Spirit of St. Louis (1957): Enthralling & Infuriating

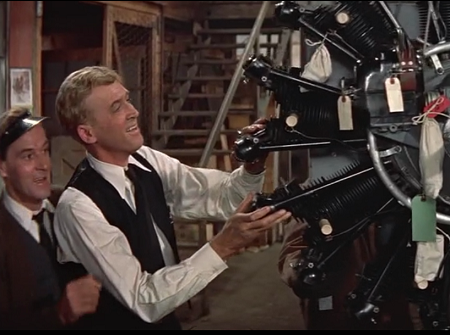

The first half of The Spirit of St. Louis, Billy Wilder’s ode to Charles Lindbergh, is engrossing. It’s even that rarest of traits in a biopic: fairly accurate. The scenes of his airmail days capture the impossible bravery of America’s early pilots and the primitive conditions under which they flew. Wilder conveys each stage of Lindbergh’s struggle beautifully: The search for funding and a plane for the epic NY-Paris flight, the near-universal doubts about his fitness for the attempt, the rush of finally finding a team to build that plane, as eager to prove themselves as he was.

Until just after that terrifying take-off, I couldn’t believe the film hadn’t earned more praise than it had.

That’s why the clunky transition into the flight–Lindbergh (Jimmy Stewart) gabbing with a fly–shocked me enough to stop the film, ponder what had gone wrong.

It wasn’t the cheesiness of the fly talk; after all, Raymond Chandler had managed to make a similar conversation in The Little Sister downright poetic. It was that everything about the first twenty minutes of the famous flight confirmed my fears: Wilder would definitely fail to make 30+ hours of sleep deprivation interesting, and his attempts to do so would not only grossly misrepresent his subject’s character, but Lindbergh’s whole purpose for making the journey.

Given, Wilder had quite an obstacle: How do you convey hours of reflection without awkward voiceovers? How do you enlighten viewers about the brilliant, reserved, limelight-averse, notoriously elusive Lindy with so little narrative space? That’s why Stewart was chosen, I thought. Wilder must have hoped the actor’s folksy geniality would while away the minutes, make us forget that the star was twice Lindy’s age, and about 100 times as charming. (If you doubt this comparison, check out Bill Bryson’s hilarious depiction of Lindbergh’s social awkwardness in One Summer: America, 1927.) The autobiography on which the film was based illuminates just how much Wilder miscalculated, and just how his still very worth viewing first half could have been redeemed in the second.

The Flashbacks

The Pulitzer Prize-winning book moves from flight to memory throughout, as the film does, but the latter’s flashbacks have a homespun, aw-shucks feel to them, with Lindbergh as a kind of lovable oaf who survives only due to luck. In one flashback, he buys a plane he can’t fly, utterly unconcerned about his lack of skill. The scene plays for comic relief, but painfully reinforces everything that Lindbergh stood against: recklessness.

Lindbergh was daring, yes, but cautious and calculating. When the flashbacks begin to appear in the book, he uses them not to illustrate character or give the reader a lovable feeling toward him. No, they explain his success. Here’s a moment of danger, and here’s the experience that prepared him for it: earlier escapes, his training as an instructor, his previous discoveries of flaws with his planes. His whole mission was to disprove that air travel was suicidal daredevilry because otherwise why pave runways? Why install lights for landings? Why allot money for research and development?

When Stewart actually pored half the canteen of water on his face—twice! —I nearly shouted at the screen. The real man was apportioning his own water in dribbles. Had anyone involved with the writing of the film read the book? “Lucky” Lindy put more thought into one move above or below the clouds than the writers did into his entire characterization. (Wendell Mayes co-wrote the screenplay with Wilder, and Charles Lederer was given adapting credit.)

Was Lindbergh lucky? Of course. But that isn’t the primary reason he succeeded. His competitors for the NY-Paris flight–those few who survived–were hundreds of miles off course, with safety features and luxuries he lacked. Lindbergh landed on his intended airfield early based on dead reckoning—no radio, no sextant, no help. How disappointing that the filmmakers would buy the “Lucky Lindy” headlines, and miss the far more interesting man.

The Moments of Danger

Lindbergh almost died innumerable times on that flight across the ocean, but Jimmy Stewart’s wide-eyed panic in no way captures Lindbergh’s icy calm. Interestingly, the pilot forced himself to calculate how to handle various frightening scenarios not out of panic, but to stay awake. He discovered that pleasant thoughts soothed, and thus led him to sleep. Plans to land on Arctic waters kept him alert—and alive. If Lindbergh really were as shot through with anxiety as the film implies, how could he have been a professional parachuter, as he was at the start of his career? A wing walker? (Tellingly, Lindbergh even dismisses the dangers of this part of his history, analyzing how safe both jobs could be with the right team.)

Oh, Jimmy…

I love Jimmy Stewart. Maybe if it were just the age, or the accent, or the personality. But it was everything: The talking aloud. The boisterous shouts. There’s a deafening, tone-deaf, overacting feel to nearly every word in the second half of the film.

Lindbergh was not Jefferson Smith or George Bailey. Effusiveness, goofiness—how widely these traits miss the quiet, introspective, highly scientific man that Lindbergh apparently was. I suspect this hamming was under protest: Stewart’s own distinguished flying record in WWII suggests he was far too acquainted with pilots to misstep this badly without directorial intervention.

Perhaps I wouldn’t have been so disappointed in the depiction of the flight, had the film not been so brilliant in the first half. But I kept thinking about what could have been: What if the film had ended at takeoff? Why try to put onscreen so much of a reflective book? Like The Great Gatsby, another notoriously hard to film text, the ideas are paramount here: Lindbergh’s meditations about God, about power, about nature and loss and risk.

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger could have attempted an arty take on Lindbergh’s thinking. But Wilder, the storytelling genius, should have stuck to action, and let us end with that lovely image that he conveyed so perfectly: of Lindbergh weighing the current against forecasted weather, his chance to beat the competitors versus his sleeplessness, the muddiness of the airfield versus its length, and then deciding to go, and with a few laconic words to the panicked faces around him, pushing off into the sky.

This post is part of the Classic Movie Blog Association’s fall blogathon. Go here for fantastic entries on films highlighting planes, trains, and automobiles. You can also find an eBook version of the blogathon with many of the group’s entries, including mine, at Smashwords (for free) or Amazon for. 99. All funds for the latter go to the National Film Preservation Foundation.