Breakfast at Tiffany’s: Why the Movie Blew It

Let me be clear: Nothing is wrong with Audrey Hepburn’s sparkling portrayal of Holly Golightly. It’s the only reason to watch Breakfast at Tiffany’s, witnessing this character’s charms (besides the obvious joys of the fashion). And though certainly a tamer version than the book’s Holly, she is every bit as interesting.

That said, fans of Truman Capote’s book have many pains in store as well as pleasures. It is truly a masochistic act to watch what becomes of favorite novels on the big screen, much like our drive-bys of houses where we once lived, when we go to see what they’ve DONE to them: a purple paint job, a favorite Oak felled.

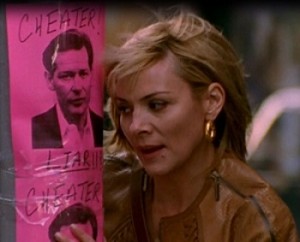

In the case of Breakfast at Tiffany’s, it isn’t the racist cameo that most strikes me, painful as it is. It’s the way the film took the sensitive, interesting, platonic-toward-Holly narrator, and chose this to portray him:

Now, I enjoyed Col. John “Hannibal” Smith and his band of A-Teamers as much as the next 10-year old. But in terms of personality, it’s difficult to imagine a bigger dud than George Peppard as Paul/Fred in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. I’m supposed to like this smug kept man who has memorized his book reviews and barks about his talent? To see in him the sensitive narrator from the novella, who is torn up by Holly’s critique of his writing? The man who is proud of the little apartment he’s obviously scraped together to afford?

I shiver to think of Holly’s twinkling self reduced to trying to prepare this dud the right flavor of chicken wings. As I watch him interact with her, I imagine William H. Macy screaming, “Where’s my dinner?!” in Pleasantville and wonder why Hollywood thinks I should root for them as a couple, why I should somehow imagine this union as right for her, as I’m clearly intended to do. That flat voice and judgmental attitude would squash her spirit within six months. True, he does laugh when she screws up a dinner for him:

But it’s still courting time, and Holly knows him well enough to be concerned about her mistake. Paul/Fred is only likeable when he’s acting as a friend to her and others, not as a would-be lover. Romantically, he’s far too conventional to suit her.

Paul/Fred, aka Col. Smith, assists Doc, aka, the Man Named Jed

I know I shouldn’t be surprised at this dreadful botching of the story. Hollywood loves a romantic comedy (as long as it’s between young, single, heterosexual characters), and, just as now, they don’t trust us to storm the theaters to watch a friendship. Yet when people recall this film, it’s Holly at the window of Tiffany’s they remember.

Why? Because this story was never meant to be about love—or really even friendship. It’s about the charms a big city represents to those of us from less thrilling hometowns, and how an insider—in this case, Holly—can show us how to make the most of the place, to be a part of it, to belong.

Here’s a favorite passage from the book: “Once a visiting relative took me to ’21,’ and there, at a superior table…was Miss Golightly, idly, publicly combing her hair; and her expression, an unrealized yawn, put, by example, a dampener on the excitement I felt over dining at so swanky a place.”

Holly has already arrived, while Paul/Fred is always seeking social acceptance. In the film, she upstages him from the start, with a powerful whistle for a cab, the kind he never could master.

Near the start of the book, the narrator (Paul/Fred) spots Holly dancing in front of a saloon in a “happy group of whisky-eyed Australian army officers baritoning, ‘Waltzing Matilda.’ As they sang they took turns spin-dancing a girl over the cobbles under the El; and the girl, Miss Golightly, to be sure, floated round in their arms light as a scarf.”

What I felt reading both of these passages was recognition: that first heady gush of love that comes to so many of us even walking down the streets of a city we (unbelievably) can call home. For me that city was San Francisco; even the sad little shops of junk, the catcalling loafers, the dirty steps of the subway could give me a rush of joy. I actually lived here. I was sometimes even asked directions. I remember admiring those girls who had the city figured out: who knew the quickest subway routes, the quirky former-salon bars, the mystery to achieving urban-chic. Those girls who hosted and were invited to the best parties, gatherings held in wineries and with themes….Oh, what magical girls they were.

For Holly, of course, the thrill of the city is represented by a beautiful jewelry shop. But for Paul/Fred—and for so many of the rest of us—it’s captured in Holly herself. She is that woman who actually does all the impulsive, New-Yorky things, who represents life in the city for the rest of us (much as Carrie Bradshaw still does for tourists today).

And by being initially an outsider herself, she gives everyone hope that they too could be like Holly one day. In the beginning of the book, she’s disappeared from the narrator’s life, but been maybe spotted by others, and to me, that opening, the desire to see her again (or maybe the time in his life she recalls), captures the allure of passing friendships.

An older, more mature Holly couldn’t possibly have the same impact. She’s charming in part because all of her affectations are intact, because she’s young enough to believe that tri-colored hair and a lack of furniture make her special, interesting. And those beliefs—not her traits or behaviors themselves—make her so.

She’s as much of an ideal creation as Gatsby ever was, and lovely, like him, because, as her former agent says, “She isn’t a phony because she’s a real phony. She believes all this crap she believes. You can’t talk her out of it.” If Paul/Fred married her or otherwise knew her for the rest of his life, many of those beautiful illusions would disappear, and everyday humdrum qualities and cynicism would surface. But he doesn’t (in the novella), so they don’t, and so forever Holly will represent to him—and to us—being young in the city.

Which is why you should skip over the first twenty-five minutes of the film to get to the party, and right when it’s starting to look like these two might actually get together, shut it off. It’s like Carrie Bradshaw moving to Connecticut and complaining to her husband about the kids’ laundry piling up. We don’t need it. We don’t want it. Let us keep remembering Holly taking in the city, as she knows so well how to do…