Talented poet and screenwriter, martial artist, and classics enthusiast Brian Wilkins agreed to guest post for me as part of The Sword and Sandal blogathon, hosted by Moon in Gemini. Check out his wonderful tribute to fight scenes below.

Sometime in 1998, I sit on the floor in my living room watching John “Kickboxing is the sport of the future” Cusack eject Benny “the Jet” Urquidez into a wall of lockers. He then proceeds to tattoo those locker numbers into Benny’s back several times with his foot. After some athletic grappling, the two fumble at each other’s skinny ties and Cusack jams his pen into Benny’s throat. I am overjoyed: Grosse Pointe Blank is everything a boy could wish for.

“Mom,” I say to the horrified woman behind me folding laundry who thought “light action comedy” would be a great choice for family movie night, “I think I want to do that. “

“I would pray you out of it,” she snaps. Mothers in the south can definitely snap and mention prayer in the same breath.

“What? Why?”

“You tell me you want to be an assassin because of a movie and you think…”

“Not an assassin, Mom! Geez. A fight choreographer.”

This comeback mollifies — but not much: “As long as you finish college.”

***

I finished a lot of college and never became a choreographer for anything beyond amateur productions of Shakespeare, but it’s hard to say who I would be without fight scenes in movies. I fenced because of The Princess Bride. I fell in love with Karate after watching Daniel-san wade through a series of talented black belts who inexplicably led with their faces. I even tried to land a crane kick at a tournament: once. I studied epic poetry in grad school because of 13th Warrior.

So when my friend Leah asked me if I’d like to contribute something for this blogathon, I jumped at the chance to look at the fights in gladiator movies. And not just any fights, but material from before Bruce Lee one inch punched his way into America’s heart and everybody was kung fu fighting. What did fighting look like in classic sword and sandal flicks?

Awful. It looks awful. It looks like America (except for James Cagney) couldn’t take a cardboard cutout prior to 1968. Honestly, watching films like The 300 Spartans must have given comfort to our enemies. I don’t know why the Russians didn’t invade.

And while I think even Alexander the Great couldn’t drink Spartans into being entertaining, it actually provides a solid rubric for what makes a good fight scene. It just doesn’t know that’s what it’s doing. Seriously, folks, I don’t think the director had ever heard the word phalanx. The best fight scene in the movie is when Diane Baker judo flips an overly amorous Greek shepherd.

***

Early in Spartans, Persian King Xerxes (David Farrar) argues with traitorous Spartan king Demaratus (Ivan Triesault) over Spartan valor. When Demaratus defends it, Xerxes suggests a fight to the death between Demaratus and a Persian swordsman. I suppose this is because Demaratus is so tiresome Xerxes would rather have him killed and be lost in Greece than listen to him flap his cheeks anymore about Spartan values. I felt that way. The two champions draw their blades in what seems an interminable fight with bowie knives. Xerxes demands, along with the audience, that they hurry it up. Quickly, death comes for the Persian, and Xerxes concedes, much to his boredom, that Spartans can fight.

Let me check my notes for this scene…oh, I just wrote, “WHAT?” about 15 times.

Two guys in tunics rolling around on dinner tables with plus-size steak knives isn’t an epic scene. There’s nothing to distinguish their fighting styles from each other, no real costuming, nothing resembling martial talent — if a fight scene looks like your kindergartner was filming themselves after raiding your closet for costumes, something has gone awry.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not advocating for historical accuracy, but just the exotic fantasy of history. I don’t care, nerds, that Russell Crowe stepped into a stirrup in Gladiator, so long as his wolf skin cloak looks really fabulous while he does it.

But just as important to style, there must be stakes for the viewer. Demaratus is a cowardly traitor: why do we care if he dies? Even this dude’s Spartan mother would spit on his corpse rather than shed a tear over not hearing more of his mind numbing dialog. Nameless Persian Thug #1 is no better. If I can’t feel passion or fear or even a soupcon of lust, why am I watching?

The plot must motivate the action as well. We have to learn something about character in this scene and the logic of the movie must give impetus to the conflict. It’s a bit like a song in a musical: the truth that can’t be said must be expressed and it must change the world we’re seeing. The correct ending in this fight scene was to have the Persian kill Demaratus. Instead, we’re now convinced the Spartans are being underestimated by Xerxes and that they’re nearly invincible. I found myself rooting for the Persians, underdogs that they were.

***

Demetrius and the Gladiators (1954) is like all of the strange pseudo-christian elements of Ben Hur wrapped up in one hell of a bogged down film.

This sequel to The Robe continues in that proud tradition, peppering in a few action scenes with Victor Mature to prod the viewer awake. It made the studios a lot of money, but I can only hope that was due to a paucity of action films…what’s that? Seven Samurai came out the same year? Well, screw it, 1950s America just loves misogynistic Christianity. Shame on you, 1950s. Shame.

Still there are elements in the fights in Demetrius that have potential. Take this clip, where Victor Mature’s Demetrius is throwing away his Christian values to avenge his girlfriend who was accidentally killed (but not really, there’s a magic robe that brings people back to life) by knuckle dragging gladiators at a party. Now that those “turn the other cheek” gloves are off, we can get some real fighting! Good thing her (apparent) death paved the way for some real entertainment! Or something like that.

You may have noticed that Mature uses his shield like a kid with a trash can lid storming the kitchen. I put that down to the vices of the choreographer, Jean Heremans, a fencing champ most noted for choreographing Scaramouche (not just a line from Bohemian Rhapsody, folks). His refined modern fencing style makes perfect sense in that 18th century setting, but it fails the style of the sword and sandal motif. Treating fighting as if it is fencing is the real dereliction of this period of choreography. I can only assume it comes from the same instinct that yearned to put a steak dinner into a pill: progress knows best.

Notice also the curious way of holding the sword with the palm down and the sword to the side, almost a foil fencer’s seconde parry. It feels out of place as a guard with short stabbing weapon and will likely get it smacked out of your hand — just in case you have to fight someone with a trident who knows what they’re doing. Despite a nice moment of dual wielding, the style doesn’t offer much excitement or novelty.

However, in terms of stakes and spirit this fight actually picks up the pace a bit. While I would have preferred any other reason for Demetrius to throw away his values and dig into fighting, his existential crisis adds a tangy zip to the clashing shields. This fight will change his destiny as a character, adding a thrill to what we’re watching. Revenge giving permission to the viewer to sanction violence, while also showing a character’s descent after the fact, and redeeming the character with a deus ex machina (almost literally) reeks of cliché, but that doesn’t mean it’s toothless. And when Demetrius actually gets clobbering a guy like Ty Cobb on opening day, we feel relief because the action initiates the structure of the story. And we like it because the choreography matches the moment and the weapons a bit more: freer and more direct.

But if you’re looking for a more nuanced examination of violence, watch Seven Samurai. Actually, if there’s one lesson you should take from this review, it should be “watch Seven Samurai.”

***

For a taste of a film that lets style guide the way, there’s always Jason and the Argonauts (1963). Ray Harryhausen’s special effects are legendary, precisely for their ability to create a world that, despite having a giant bronze statue really need a hair pin, feels real. In fact, unlike much modern CGI, it’s the actors that feel less real than the animations: a testament to the quality of both.

This clip is so iconic it really needs no introduction.

There are a lot of things to love about this scene, but there are certain moments that stand out for me.

- The war cry the skeletons give just before charging after Jason and his compatriots: it immediately moves the bony little bastards out of the realm of slouching zombie and into something else entirely.

- The skeletons get into fighting stances and even seem to relish stabbing the heroes. Their stances are better than anyone else on screen: hunched, menacing, preparing to do ill to the enemy. Jason looks like he just discovered swords over breakfast.

- The skeletons seem to know how to use their shields. One even hooks a shield into the sea.

But most of all, this scene understands the equipment being used. You can’t stab a skeleton risen from the sown teeth of a hydra! Everyone knows that! Except Jason, who tries it at 3:36 in the clip. And that’s the core of why this scene is great: the heroes have to improvise and start using dodges, feints, throws, and even clubbing the skeletons with the shields (although why no one can seem to stab and block simultaneously is beyond me. I guess we’ll have to wait for Troy).

Though we learn little about the spirit of the characters beyond the fact that Jason is quite content to flee and let his friends die, the stakes in this scene feel high. Perhaps it’s just that as humans we must root for those of us still covered in skin. Perhaps it’s that this idea was fished out from the Hieronymous Bosch corner of the unconscious. But either way, Ray Harryhausen was a genius I wouldn’t have wanted to fight in any place with a sandy floor.

***

There’s no mystery in my mind about the best of the sword and sandal genre. It’s Spartacus, hands down. Ignoring the politics, history, and its place in film for a moment, though, it’s a damn fine fight film. It even has a great training montage! Look, a spinning practice dummy with a mace on it! And there, a spinning blade of death machine! Even face painting!

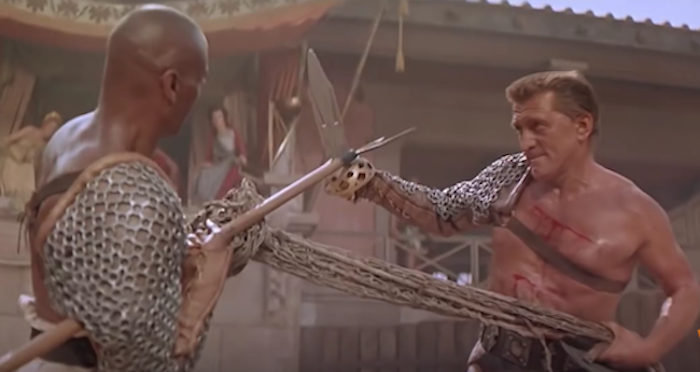

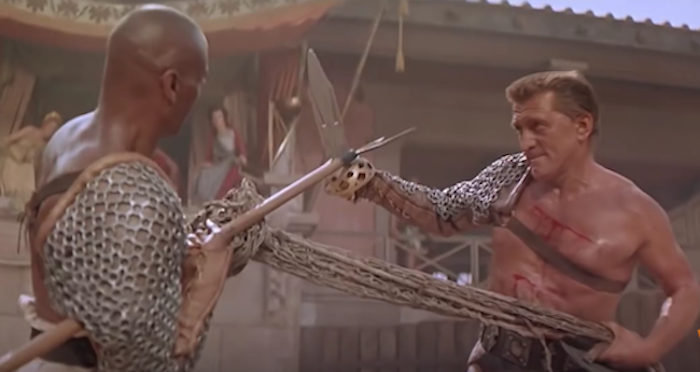

To set up the scene: Spartacus (Kirk Douglas) has been paired with the more experienced gladiator Draba (Woody Strode), to fight to the death for the amusement of visiting nobles, particularly Crassus (Laurence Olivier).

Good movies work as fractals: little gems of the overall message replayed again and again to make one larger, faceted meaning. This fight tells you all you need to know about the movie, and the tragic but worthwhile attempt of compassion and brotherhood to fight back against a rigged system. It teaches you to ask who the enemy really is. This is a fight between Drapa and Crassus, first and foremost. And the mild annoyance with which Olivier kills Strode, with his distaste for the blood spatter rather than the action of murdering a human being, drives the nature of that character home.

But that moment is preceded and earned by some rather decent fighting. Strode was far too athletic to not take advantage of his size and is a perfect pairing with the trident. Douglas is a little too lightly armored, actually. He should have at least a helmet. The lack here is better than just artistic license and wanting to see the actor’s face: it shows even more how dangerous this fight is for Spartacus, making the act of compassion even greater.

Though he does hold his own. He’s always driving forward, trying to cover the distance and his lack of technique with enthusiasm. And while it ends with a rather spectacular boot to the ribs, Spartacus fights with just enough skill to lose well, which helps momentarily suspend our belief that just because the movie is called, “Spartacus”, he’s unlikely to die at the first real fight.

Though you could wonder if the Romans care at all. The audience talks over the two men fighting to the death at first, allowing us to condemn the Romans for being that annoying couple at the movies who explain the plot as the movie progresses. The inclusion of the audience into the scene makes the points of the movie so well, and asks us to question our own participation. It calls us to act with mercy and courage.

***

The complaint you’ll hear most often about these fight scenes is that they aren’t realistic, by which most people mean gritty or brutal. Fights in real life aren’t as spectacular, they argue, or as technical, and they don’t tell us much about the nobler parts of our role to play as humans. This lack of realism somehow damages the truth a fight may offer. Sometimes they’re right: the samurai master is killed by a punk with a knife at dinner, people windmill at each other over bar stool rights, and most fights are just attacks by predators or drunks.

But that’s why we come to the screen in the first place: to dream our better selves into being. A fight, even a silly one against skeletons, can show us how to be brave, to stand against impossible odds. When asked to surrender by the Nazis during the Battle of the Bulge, Gen. Anthony McAuliffe sent back a telegram with a one word reply: “Nuts!” You can’t write better dialog than that. And that’s what I say to folks who can’t see the beauty in the ringing steel, the athletic achievement, and most importantly, the spirit of laying it all on the line. Except I want to add “you,” and “are.”

by Brian Wilkins

This post is part of the Sword and Sandal blogathon. Check out the other entries here.