This post is part of A Shroud of Thoughts’ The British Invaders Blogathon. Check out all the great entries!

Why did this film about the terrible choices a woman must make for her art inspire generations of ballerinas? Every little girl raised on Hans Christian Anderson knows that Karen, the red shoe-shod girl, doesn’t fare well: as punishment for her vanity in choosing red shoes for her confirmation (and similar sins), Karen can’t stop the shoes from dancing, can’t take them off, can’t go to church, can’t even prevent her detached legs from dancing when they’re cut off and replaced with wooden ones. Only when she truly feels remorse does she find peace—in death.

Surely then, a film about these shoes won’t bode well for the heroine, Vicky Page (Moira Shearer), as indeed, proves to be the case. The aspiring ballerina’s fierce impresario, Boris Lermontov (Anton Walbrook), expects unwavering commitment to dance. Vicky arrests his attention and is allowed into his troupe mainly because she seems to possess it:

“Why do you want to dance?” Lermontov asks when he meets her.

“Why do you want to live?” Vicky answers.

“I don’t know exactly why, but I must,” he admits.

“That’s my answer too,” Vicky answers.

His prima ballerina’s nuptials lead the fiery director to boot her out, and usher Vicky in. He’s not interested in any dancer “imbecile enough to get married.” “You cannot have it both ways,” he explains to his choreographer. “A dancer who relies upon the doubtful comforts of human love will never be a great dancer, never.” Vicky is soon in training for Lermontov’s new ballet, which is based on the Hans Christian Anderson tale, with a company skeptical about her abilities and self-doubt growing under everyone’s exacting standards.

She relaxes when The Red Shoes becomes a spectacular smash, but conflict soon arises in the form of the ballet’s young composer, Julian Craster (Marius Goring), who has fallen for Vicky, and she for him. At this point, we viewers are still happy: she’s gotten her role, as has Julian, whom we’re also rooting for; she’s a hit, as is he; they’re in love, and have earned the respect and affection of the rest of the troupe. But then Lermontov finds out, and she has to choose: greatness with him, or mediocrity with Julian (only minor roles, minor ballets for her). And like every woman before her, this choice between love and ambition will not be an easy one, and she will be tortured either way.

Why then, did this tragic film result in so many enthusiastic young ballerinas? I have a few theories on that, having been in ballet from ages 5-12 myself, and seen this movie when I was gobbling up Noel Streatfeild’s Ballet Shoes series.

For Young Girls, It Wouldn’t Have Been a Tough Choice

Julian is a likeable guy (for most of the film). He’s ambitious, cocky, devoted to his art, smart. He stands up for himself when he’s cheated; he’s supportive, sweet, and appreciative of Vicky as an artist, as he demonstrates during their loveliest moment together, when he envisions a time when a child will ask him as an old man where he was most happy, and he’ll answer this moment with Vicky: “‘What?’ [the girl] will say. ‘Do you mean the famous dancer?’ I will nod. ‘Yes, my dear, I do….We were, I remember, very much in love.’”

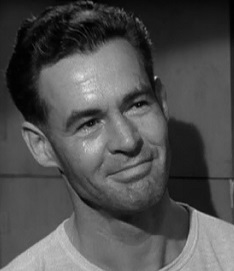

But let’s be frank here: Aside from the romantic streak, these are the types of traits women long on the dating scene may appreciate, but are not the type to win over pre-pubescent girls. This is not the kind of face girls’ dreams are made of:

Without the conflict, no tragedy. And after all, even those girls who dream of perfect love and great achievement know a ballerina’s career is short. Their gossiping friends in the dance company will tell them so (if they’ve made it that far). And if they’re still beginning, well, they will learn as much after a day with some dance flicks: The Turning Point, Center Stage. Is it so impossible for the young dreamer to think she’ll simply fall in love later, as the actress (Moira Shearer) herself did in her mid-twenties after her greatest dancing successes?

The Caliber of the Dancing

The pet peeve of dancing enthusiasts is when films substitute allegedly good actors for good dancers—because Jennifer Beals, my friends, sure did have acting chops. Perhaps I would understand this choice if any of the actors and actresses selected were talented.

Take, for example, Center Stage (2000), which played it both ways, inserting a few actors among real-life ballet dancers to elevate the film’s quality. While the result is good dancing, but an array of poor acting performances, the worst among the bunch are Zoe Saldana and Susan May Pratt, who were chosen for their supposed dramatic skills; the latter can’t even manage graceful walking. People, no dancer has ever regretted watching a Fred Astaire film, and the man was at best a passable actor. No dancer says, “I would have enjoyed that movie if he could act,” even if an occasional person among the general audience does.

The Red Shoes, like the Rogers-Astaire films before it, did something more than highlight amateur beginners. It featured world-renowned ballet dancers and choreographers. Léonide Massine, who plays the choreographer (Ljubov) in the film, was a choreographer of nearly the status as George Balanchine. He created and acted the part of the shoemaker in the ballet. The replaced prima ballerina, Boronskaja (Ludmilla Tcherina), was in real life a prima ballerina in France.

And Moira Shearer? She danced for both Balanchine and Massine as a principal in the Sadler’s Wells (later the Royal Ballet), along with, you guessed it, that little-known ballerina Margot Fonteyn, whose costar in the company choreographed and played the male lead in the ballet within the film, Robert Helpmann.

Helpmann, Shearer, and Massine

Choosing such ballet luminaries didn’t hurt directors/writers Emeric Pressburger and Michael Powell’s movie; they were even lucky enough to find in these stars acting skills as well (which we rather expect in our greatest ballet dancers).

The Red Shoes’ most famous ballet itself is stunning, surreal, inventive and truly impossible to put into words, capturing the darkness of the fairy tale and all of its creepy, moralistic, vaguely misogynistic undertones, and giving Shearer the chance to demonstrate just why she was considered by some to be Fonteyn’s equal. It probably didn’t hurt that the film was scored by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.

The Realism

The movie is known for its surreal use of color and special effects and for a riveting performance by Walbrook as Lermontov.

It’s recognized now as ridiculously ahead of its time; one shivers to think what an American studio would have done with the same material in 1948: the starlets they would have chosen, the bizarre beauty they would have stamped out.

But by any standards, this film captures ballet as it is lived as well: the punishing practices, the demand for perfection, the colorful personalities, the scary choreographers and directors. I didn’t even make it into the company in my school, but I was terrified of the man who was our head. I’ll never forget his sharp eyes on me when I missed a move in The Nutcracker, nor his poise, which was every bit as still and intimidating as Lermontov’s. And this was a director of a small company in a minor city.

Vicky (Shearer) rebuffed by Ljubov (Massine)

The film, however, captures more than the tribulations of a dancer’s life. It conveys too the joy of the right move, of building toward something creative together, of earning not just the admiration of a crowd, but of those whose judgment you know to value.

Colleagues in film and on the stage: Helpmann, Massine, and Shearer

And it portrays the thrill of those impossibly lovely gestures, pirouettes, and leaps too, which no other experience can quite replicate.

Shearer believed the film injured her classical dance career because critics assumed she was riding on her fame from it rather than technical talent. If that’s true, I want to thank her for the sacrifice (admittedly too late). For it meant many young aspiring ballerinas like me, who would never go very far in dance, would understand in watching and re-watching The Red Shoes just what had made those hours in the studio worth it for us. Yes, it was literally a pain to practice (I feel a cramp in the arch of my foot just remembering those pointe shoes). And it hurt even more when it was time to let ballet go. But look! Just watch Vicky.

Why wouldn’t you want to be a part of that, even for a little while?