State of the Union: the Wish Fulfillment Edition

This post is part of The Great Katharine Hepburn blogathon. Be sure to check out the other entries!

The political satire in 1948’s State of the Union feels disturbingly fresh. Replace a phrase or two, and presidential nominee Grant Matthews’ (Spencer Tracy’s) speeches on the “working man” could fit into the Occupy Wall Street movement.

The film’s title, however, refers to not only what’s rotten in the state of the nation, but in the marriage between Grant (Tracy) and Mary Matthews (Katharine Hepburn).

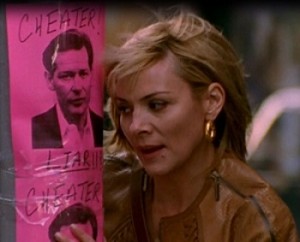

Sexy newspaper publisher Kay Thorndyke (Angela Lansbury) has seduced Grant with the aim of pitting him against her dead father’s political rivals.

Mary (Hepburn) agrees to pretend her marriage is strong for the sake of the campaign, as she believes her husband a “great man,” which, if he ever were, he ceases to be by the film’s close. The movie traces his idealism crumbling under the necessity of playing the political game, thanks, in no small part, to Kay’s machinations.

The dialogue is as sharp and cynical as you would expect in a Frank Capra film. My favorite comment is when Mary snaps that the slimy politician under Kay’s supervision (Adolphe Menjou) should be happy about what’s left of her own naiveté: “You politicians have remained professionals only because the voters have remained amateurs.”

The central problem of the film is how unsympathetic her husband Grant is. A self-made man with his “little guy” days far behind him, he pompously lectures businessmen and union leaders about how that little guy should be treated. Capra treats him as if he’s one of his innocents among the corrupt, like Mr. Deeds or Jefferson Smith, and it doesn’t work–Grant begins as a heel, and ends as a worse one.

And it’s hard to forget he’s betrayed a wife so cool she calmly knits while he’s doing acrobatics with his plane, handing campaign manager (Van Johnson) her bag to puke in.

Luckily, we can ignore Grant and his speechifying and pay attention to the true delight of the film: Mary and Kay facing off against one another—Mary because she loves her husband, and Kay because she fears Grant will be swayed by his wife’s morals and thus lose the election.

Just listen to how they talk about each other:

Kay: “That woman’s got to [Grant]. She’s been feeding him that to-thine-own-self-be-true diet.”

Mary: “If this weren’t my house, I could tell her someplace she has to go to…” or “…I think Kay’d be more comfortable in a kennel.”

When Mary has to invite Kay to her house to cover up the affair, she tries to avoid doing what she apparently did once before: getting plastered and throwing Kay out. This is the moment in the film when I wanted to shake Capra. That’s the scene you left out???

We do get treated to seeing Mary drunk in defiance of orders from Kay and crew.

But I kept wishing for a The Women-style face off; the heroines are so powerful and interesting that in comparison, the men in the film (with the exception of Johnson and Mary’s butler) seem a waste of screen time. Luckily, the women are so fun to watch that they revive and redeem the film.

At one point Grant’s barber shares his wife’s conviction that a woman should be president. “That’s silly,” responds Mary. “No woman could ever run for president. She’d have to admit she was over 35.”

Though the quip is funny, no line coming out of Hepburn’s mouth was ever less convincing. Those who know anything about Hepburn realize she had confidence to spare, felt comfortable aging in front of the camera, and would have run for any office if she’d felt like it. Mary clearly has Hepburn’s spunk, and after all, a woman had run for president more than 70 years before this film, another woman with considerable moxie.

Would Mary have won? Of course not. But what speeches she would have written!

And for Capra not to give Kay more time in the film is criminal. Watch her command her editors to publish filth about all of the Republican candidates so that their united hatred for one another will make them choose her man (Grant) at the convention. That icy stare you recognize from The Manchurian Candidate (1962)? Yeah, this is a woman who could make it to the White House today for sure. She’s a predatory villain as thrilling to watch as Claire Underwood (Robin Wright) in House of Cards.

It’s probably enough that a film in 1948 starred such strong actresses playing powerful roles. I shouldn’t wish for what could have been, these two really facing off against each other, maybe even running against each other for office.

But what a film that would have been.