Ray Milland & the Columbo Surge

I adore that Columbo is experiencing a renaissance with younger audiences. Gabrielle Sanchez attributes it to youth’s “clamor for more murder mysteries that skewer the rich.” Not hard to believe given the dominance of The White Lotus and Succession.

Columbo’s viewership had already been climbing steadily during quarantine, thanks to its soothing appeal. Then Rian Johnson embraced his own Columbo fandom with the Natasha-Lyonne helmed tribute series, Poker Face, this year, guaranteeing that his many young Knives Out fans would follow his wake back to the short man in the long raincoat the rest of us have been loving for decades. (I knew anyone who created Brick would be a classics fan.)

All of this fervor in turn brings new audiences to the classic movie stars we bloggers love, from Janet Leigh to Faye Dunaway to Myrna Loy to Celeste Holm. Even Don frickin Ameche (I’m a big fan of 1939’s Midnight). And of course, this fervor brings us to the suave, compelling Ray Milland, who appeared in two Columbo episodes—both early in the show’s run, when it was at its best.

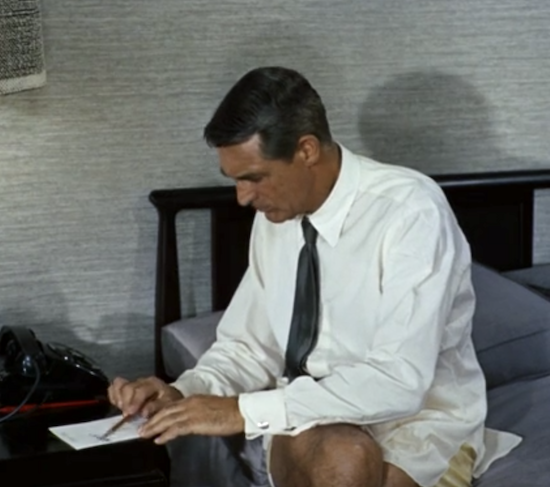

I’ve often been curious about Milland. “The poor man’s Cary Grant” I read once in reference to him (though it might have been Melvyn Douglas). The dig was especially unfair since Milland was sometimes preferred to Grant: in the casting of Bringing Up Baby, for example. He was chosen over Grant for Dial M for Murder, due to salary or villain-casting worries. But the dig is fair in one sense: Grant was an icon everyone knows still today, and Milland?

“Who is that?” said my mother (echoing every other person I asked).

And yet, even those who don’t know Milland will catch a whiff of Grant. Close your eyes when watching a Ray Milland film, and for a minute, you’ll mistake the Welsh actor’s Mid-Atlantic accent for my favorite Bristol-born actor’s. Watch, for a moment, Milland move, and his easy grace and debonair expressions will trick your eyes too—as will his sharp wit and self-amusement.

And his slim build, height, dark hair, and air of confidence and wealth will throw you. As a Matinee and Mustache tumblr poster brilliantly put it, “Ray Milland looks like if Cary Grant and Jimmy Stewart had a son together after the Philadelphia Story.”

No wonder when The Awful Truth was remade as a musical in 1953, Milland was chosen to play Grant’s role.

But the Oscar-winning star of The Lost Weekend deserves to be remembered for more than just a Grant resemblance. I’ve never thought he ought to be appreciated as much for the good, but miserable-to-watch film that won him his greatest honor as for the comedies and dramas to which he leant such a light comic touch or thrilling suspense. I loved him in The Major and the Minor (1942) with Ginger Rogers, despite the issues with that subject matter. I loved him in The Uninvited, where he’s a charming, funny companion to sister Pamela (Ruth Hussey), grounding a gothic tale that otherwise would have gone too far off the rails.

And of course, I love him as the coldblooded plotter in Dial M for Murder. In fact, that film is one of my least favorite Hitchcocks but for his performance. The superiority and cool assurance he displays in that story make him an especially riveting villain. I particularly admire his character’s appraisal of the hitman’s situation, and how coolly he explains to the poor man that he simply has no choice but to kill his wife.

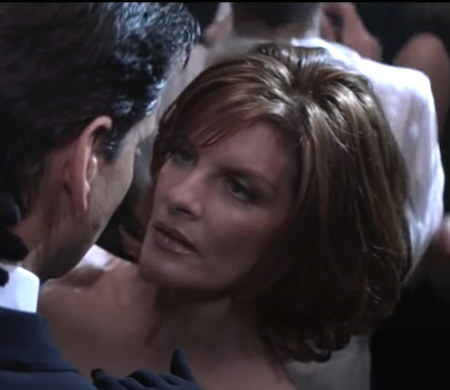

So it fits then, that in his Columbo appearances, Milland tries his hand at two different kinds of roles: in the second episode of season 1, he plays the beloved husband of the victim, displaying the charm and intelligence that made him such a draw to women in his movies.

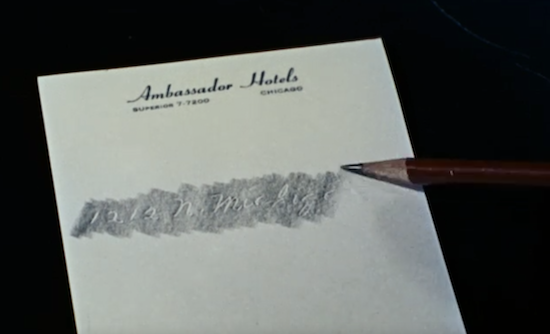

And in the second episode of season 2, “The Greenhouse Jungle,” he’s a version of his scheming Dial M for Murder villain, killing his nephew after an audacious kidnapping plot.

These episodes are such fun to watch. The first, “Death Lends a Hand,” features Robert Culp as the blackmailing private detective who accidentally kills the cheating wife of an influential newspaper owner, Arthur Kennicutt (Milland), after she refuses to give into his schemes. Columbo is a DELIGHT in this episode, playing his usual, I’m-harmless game in some of my favorite scenes. In an early moment, he not only walks into a closet instead of out a front door, but pretends to be a big believer in palmistry with a straight face. Wonderful. We get hints of Columbo’s rapscallion past. And throughout, Milland plays the grieving widower with a dignity that makes us feel for his loss. His growing appreciation for Columbo is subtly shown. The quick, almost impressionistic shots of the killing and cleanup are cleverly done. And Culp is at his irascible best.

“The Greenhouse Jungle” is a bit lengthy for me, with too many shots of cars driving, but the plot is fun to watch and the humor intense throughout thanks to an ambitious young police officer who thinks he’s outsmarting Columbo. In a wonderful scene, the young officer shows off expensive tech equipment he’s bought himself, and our favorite lieutenant quips that he must be a bachelor. I also enjoyed Columbo’s hilarious ploy of disarming Milland, an orchid aficionado, by asking that he repair his wife’s 90-percent-dead African violet. Milland has a blast playing a supercilious, judgmental, superior snob who thinks he’s come up with a genius plot. He is not as clever as the Dial M for Murder schemer, but thinks he is. Milland approaches, but doesn’t quite veer into, hamminess in the role, which makes him riveting. But my favorite aspect of both episodes is–not shockingly–Columbo’s insight and empathy.

In “Death Lends a Hand,” he shows such understanding for the man who had an affair with Kennicutt’s wife. He is surprisingly blunt with him, admitting his suspicions about the relationship right away, but also assuring him he’s not a suspect (and this time, he means it). The golf pro seems like such a nice guy, and it warms us to see Columbo treat him with so much understanding. The lieutenant is also adorably kind to the villain’s minion, right after fooling him to expose his boss.

In “The Greenhouse Jungle,” the wife of the victim is in an open relationship–which makes Milland’s character despise her and his nephew. But Columbo says he admires her for her honesty about who she is, and we believe him. It’s this lack of judgment and lack of the kind of he-man attitude toward women so familiar in other cop shows (then and now) that make Columbo always feel so modern and fresh and lovable.

And how lovely it is to see Ray Milland, an underrated actor in this day (if not in his), playing on a show that is all about the dangers of underestimating others.

This post is part of the Classic Movie Blog Association (CMBA)’s blogathon, Big Stars on the Small Screen: In Support of National Classic Movie Day! Definitely check out the other entries!

For fantastic Columbo episode breakdowns, go to Columbophile!